MAKING THE ROOM SING

Text by curator Stella Sideli Making the Room Sing, an exhibition by Amanda Camenisch and Therese Westin at Metroland Studios, commissioned by Metroland Cultures for Brent Biennial, 2022

There’s something intuitively moving and sacred in being in the space that Amanda Camenisch and Therese Westin have filled with gentle gestures and revelations. I know that this work is made by the artists over months of painting, poetry, weaving, fabric dying, voice compositions and discussion workshops in collaboration with a group of women from the Asian Women’s Resource Centre (AWRC). I think about creating that space together, and I start wondering by looking at the works.

I have missed feeling like that while walking into a show, lately; getting this immediate sense, upon entering a room, that the exploration is going to take me on a journey; that distant worlds will be imagined and experienced; that I will find myself in someone else’s body; that something is going to change a bit when I leave.

Entering the gallery is like stepping inside a dream, at first. Both the visual and aural fields are filled with pastel tones and harp vibrations; soft shapes and smooth materials populate the landscape and make it restful, serene.

Dream is a major component of the exhibition— not so much because of its abstractive, mirage-like qualities and powers, but as a dynamic tool to imagine, heal, be empowered and world-make, following from a past trauma, great distress, an agonising lived experience at the edge of sanity or beyond, a nightmare of oppressing monsters.

Dreamscape, collectively made with the women of AWRC like a lot of other works in the room, is what I am drawn to at first. It’s a wall piece containing the women’s dreams and wishes, letters to each other and to themselves, visions, affirmations.

And like in dreams, symbols are key: plant-dyed and sewn on the stolas, sea urchins, lions, banana trees, bells, shells and moons inhabit the silk. They embody the purest part of the creative subjects that originated them. Aided by the unconscious and appeared during the guided meditations, they materialise as portals, to healing and future nourishement, growth.

Sound fills the room in the meantime. The composition Elemental Tuning1, and poems, affirmations, harp arrangements developed during the somatic practice sessions in the leading up to the exhibition, match my breathing. It becomes slightly slower, as I focus on perception beyond ocularcentrism, and naturally involve the rest of the body: “lungs, heart, and liver, as knowing becomes breathing and beating”2, with piercing clarity.

Here’s how sound is a fully corporeal, intimate and unique, yet collective and cosmic experience, throughout the process of creating the works and in the works themselves. For example, from breathing/beating to voice— the primordial instrument for dissidence, protest, rebellion and empowerment; instrument of the soul, silenced or taken away, sung with hope, listened to with compassion; instrument to create connection and movement, harmonised to communicate and evolve. And from voice, to limbs and core in order to play the Four Elemental Harps: Earth Harp, Air Harp, Fire Harp, Water Harp; to absorb their waves, their healing vibrations, including the ones produced by The sleep that sleeps itself, the instrument/chaise longue in the middle of the room. I sit on it, and while Amanda plays it for me I realise it’s tuned to the notes of the vibration in my womb and spine, filling me with vital flow, leaving me dreamy and energised, grounded at the same time.

The Elemental Harps, placed in the four corners of the room, almost like to mark a field relative to the centre of a compass, follow a similar principle: a special tuning technique inspired by Indian gramma notations, connecting the harps in an unique attunement, in an exercise of listening and breaking silence which has been a key part of the process of working collectively.

Attunement is a recurring idea in the process leading up to the exhibition, together with care and compassion and enacted by playing through each other’s body, or noticing how sound moves in space, or drawing emotions and states of mind.

And it’s in attuning, in caring, in coming together as one and simultaneously allowing for different roles and levels of involvement to come up for different participants, that creative action is taken. This kind of process of collaboration is intended as an organic experience, based on non western, non extractive approaches of co-creating and relating to each other.

The idea of empowerment comes through the body too. A New Dawn, the robes-like, soft sculptures hanging on the left of the room, almost mirror the Dreamscape stoles on the opposite side and give the room a different, milder shape, through mother of pearl, illuminant reflections and gentle sounding medallion bells. These dragon robes protect and invoke the women who participated in the production of the works in the exhibition and celebrate it; they are proof of their sacredness, bringing me back to what I felt in the beginning; in a circle that makes one renewed.

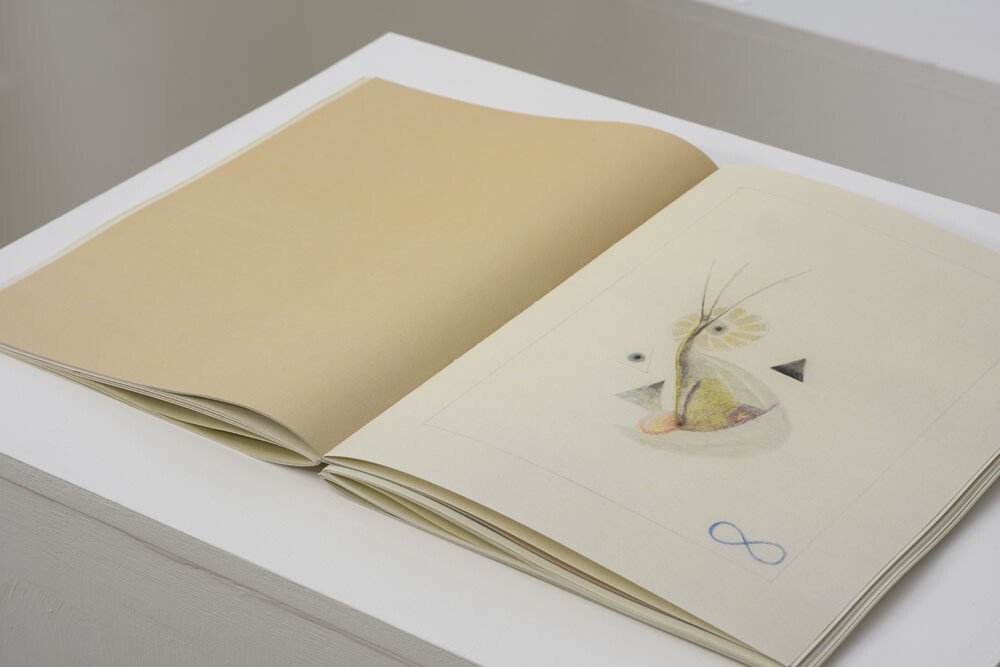

Like the elements in Dreamscape, or in the The Work Manuals book, the robes collect a series of inner images generated with a non-narrative approach to experiencing and inhabiting a space.

Making the Room Sing shows that by using active imagination as a conscious method of experimentation, and practising creativity, however we choose to do it, nourishes introspection and realisation, while forging a deeper connection within ourselves and to the world.

1 My Soothing Sounds by Claudine, Elemental Tuning by Amanda, Therese, Ilyas, Ahhh My Voice and Affirmation for Women by Claudine

2 Silvia Rivera Cusicanqui, Ch'ixinakax Utxiwa: On Decolonising Practices and Discourses